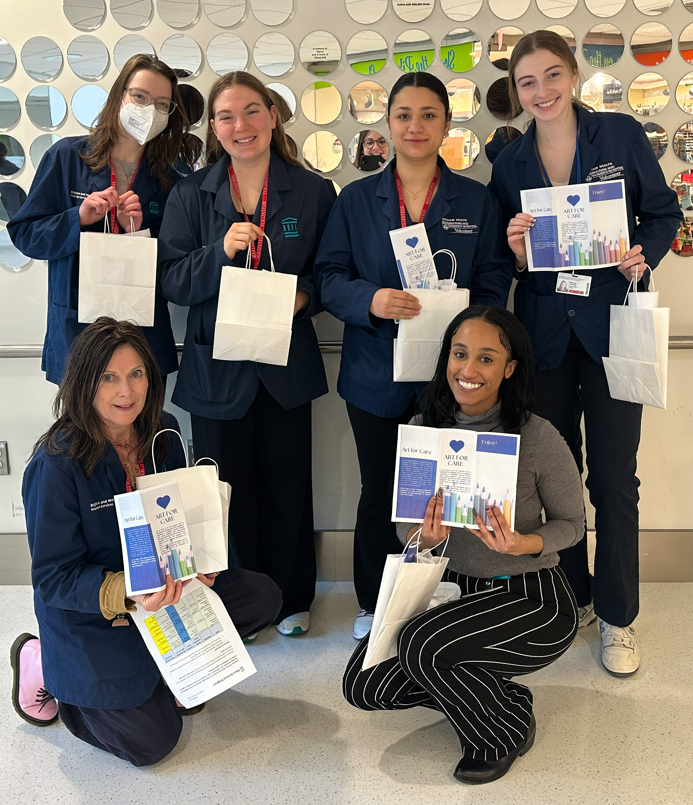

Shapiro 3 opens new inpatient unit

Nursing leaders and staff celebrate the opening day of a new inpatient unit on Shapiro 3 on Sept. 30.

With the opening of 10 beds on Sept. 30, Shapiro 3 officially became a new inpatient unit — capping off the first phase of a two-part project to transform the floor from outpatient clinics to inpatient units. Upon the project’s completion in spring 2025, it will feature a total of 21 patient beds.

The project marks the first new inpatient floor in the Shapiro Cardiovascular Center since the building opened in 2008. It is one of several efforts underway to increase bed capacity across BWH and BWFH to meet continued high demand for hospital care. By next August, when construction is completed across multiple projects at both sites, the Brigham family will collectively gain 121 new inpatient beds. New beds will open for clinical use incrementally during and after this period.

Hospitals across the country have continued to see demand for patient care outstrip capacity since the COVID-19 pandemic. The complex, multifaceted crisis has created a ripple effect across every aspect of clinical operations, from emergency department overcrowding to long delays in ambulatory access.

“We’re excited to have more beds to help meet the Brigham’s unprecedented high demand for inpatient care. This is what our patients need, and it’s been remarkable watching the team come together to make this happen,” said Kevin Giordano, chief operating officer of BWH and the BWPO and president of BWFH. “We know, however, that beds are just one piece of the puzzle. Addressing this crisis means we need to continue working on local initiatives and collaborating across Mass General Brigham to best use our collective resources.”

‘Enablers’ make it all possible

What is striking about the Shapiro 3 project is not just its outcome but also the intense coordination and collaboration that made it possible.

Through a series of nine finely orchestrated, interdependent “enabling projects,” each led by a separate project manager, teams across BWH planned and executed the many relocations and renovations. Additionally, project teams collaborated closely with affected departments not only to ensure a smooth process but also to find opportunities to enhance their working areas.

“It was a terrific team effort not just by Real Estate but also every department involved in these projects,” said Sonal Gandhi, MUP, vice president of Real Estate, Planning and Construction. “For each impacted space, staff were part of this process. We asked what they needed while leveraging the opportunity to optimize our limited space, and we incorporated that into the planning. And that’s one of the most exciting aspects of this endeavor. It really is more than the sum of its parts.”

One example of this is a new outpatient clinic at 1285 Beacon St. in Brookline that houses Orthopaedics, Rehabilitation Services and Imaging — bringing together three key clinical services in a convenient, community-based location. The clinic’s February 2024 opening depended on, and enabled, a series of other moves. To help make it possible, about half of Orthopaedics’ ambulatory operations moved out of the Hale building, which in turn allowed Brigham Circle Medical Associates to move from Shapiro 3 to Hale.

James Kang, MD, chair of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, said his initial skepticism about the impact of such a big move was quickly put to rest upon seeing the new space.

“At first, I was concerned about the potential challenges this move would create. However, after the new clinic at 1285 Beacon St. was completed, it was clear that it would deliver the same outstanding care and experience we provide at the main campus, with the added bonus of a more intimate atmosphere and convenient location within the local community,” Kang said. “As chair, I am happy that our department was able to help the Brigham make room for the much-needed additional inpatient beds. This well-organized move could not have been orchestrated any better.”

Although Patient Family Relations (PFR) had a much shorter move — across the hall on Braunwald Tower 1 to the Sharf Admitting Center — the relocation also brought unexpected benefits. The team previously shared a space with Admitting staff in the Bretholtz Center, which now houses both surgical and obstetrical admitting.

“Our new, dedicated space has given us the opportunity to connect directly with patients and families in a quiet and supportive space,” said Lynne Blech, MBA, senior manager of Patient Family Relations. “Our conference room allows us to meet directly with patients and families who walk in requesting to speak with us. Additionally, we have been able to conduct in-person family meetings and Patient Family Advisory Council meetings.”

The Admitting and PFR moves set the stage for the Shapiro 2 Family Center to relocate half of its operations to Bretholtz, which in turn enabled the Watkins Cardiovascular Clinic to consolidate its three clinics into a single, combined physical space on Shapiro 2. Previously, Watkins occupied three separate suites across Shapiro 2 and 3.

“Transitioning from three separate clinics — with three separate waiting rooms — to one large clinic with one waiting room helps improve patient, provider and staff experience,” said Greg Bloom, MHA, director of Ambulatory Operations for Watkins. “Having one check-in space has improved wayfinding and reduced patient confusion about the location of their visit. More subspecialties in one area increases real-time provider-to-provider communication to discuss complex patients. And having all staff on one floor makes it easier to handle last-minute call outs, lunch coverage and other coverage needs that occur during the day.”

Julia Mason, DNP, MBA, RN, CENP, chief nursing officer and senior vice president of Patient Care Services, expressed gratitude for the many teams involved in the planning process, execution of moves and opening of Shapiro 3 as an inpatient unit.

“Providing the best care for our patients is at the heart of these efforts,” she said. “Thank you to the many teams involved for your incredible collaboration, dedication and patience throughout this process. We remain committed to addressing capacity challenges from every angle, both as a hospital and across the system.”

Brigham and Women’s Hospital mourns the loss of Christopher Fletcher, MD, FRCPath, professor emeritus at Harvard Medical School and senior pathologist at the Brigham. Dr. Fletcher died on July 28 at the age of 66.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital mourns the loss of Christopher Fletcher, MD, FRCPath, professor emeritus at Harvard Medical School and senior pathologist at the Brigham. Dr. Fletcher died on July 28 at the age of 66.

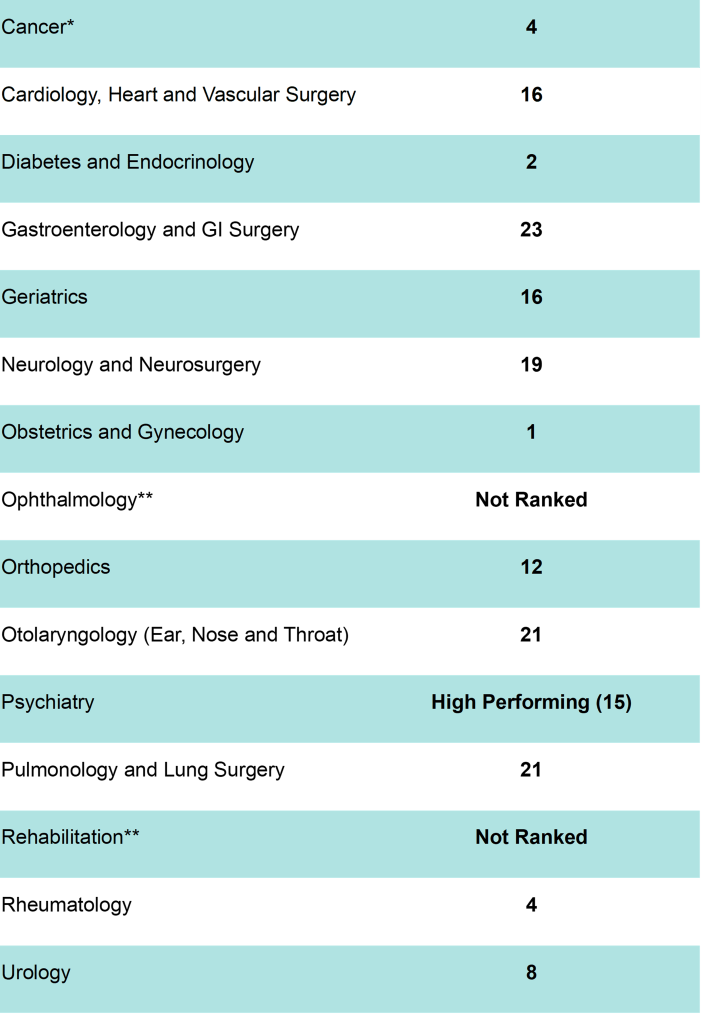

Once again, Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) was named one of the nation’s top hospitals by U.S. News & World Report in its 2024–25 Best Hospitals Honor Roll and ranked first nationwide for Obstetrics and Gynecology for the third consecutive year. In all, five eligible specialties earned a spot in the national top 10 this year, with four of those making the top five.

Once again, Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) was named one of the nation’s top hospitals by U.S. News & World Report in its 2024–25 Best Hospitals Honor Roll and ranked first nationwide for Obstetrics and Gynecology for the third consecutive year. In all, five eligible specialties earned a spot in the national top 10 this year, with four of those making the top five.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) mourns the loss of Scott B. Lovitch, MD, PhD, attending pathologist on the Hematopathology and Molecular Diagnostic Pathology services, who died suddenly on April 13. He was 45.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) mourns the loss of Scott B. Lovitch, MD, PhD, attending pathologist on the Hematopathology and Molecular Diagnostic Pathology services, who died suddenly on April 13. He was 45.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital mourns the loss of Michael Besly, a medical assistant in the Urgent Care Center in Foxborough, who died suddenly on March 6. He was 61.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital mourns the loss of Michael Besly, a medical assistant in the Urgent Care Center in Foxborough, who died suddenly on March 6. He was 61.

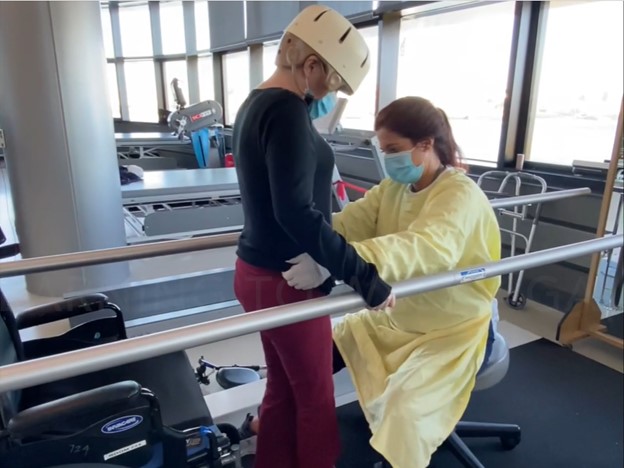

For Jocelyn Lydon, OT, OTR, not much can compare to witnessing patients get ready for discharge from the Burn, Trauma and Surgery Unit on Braunwald Tower 8.

For Jocelyn Lydon, OT, OTR, not much can compare to witnessing patients get ready for discharge from the Burn, Trauma and Surgery Unit on Braunwald Tower 8.