Blood donors serve as important lifeline for sickle cell disease patients

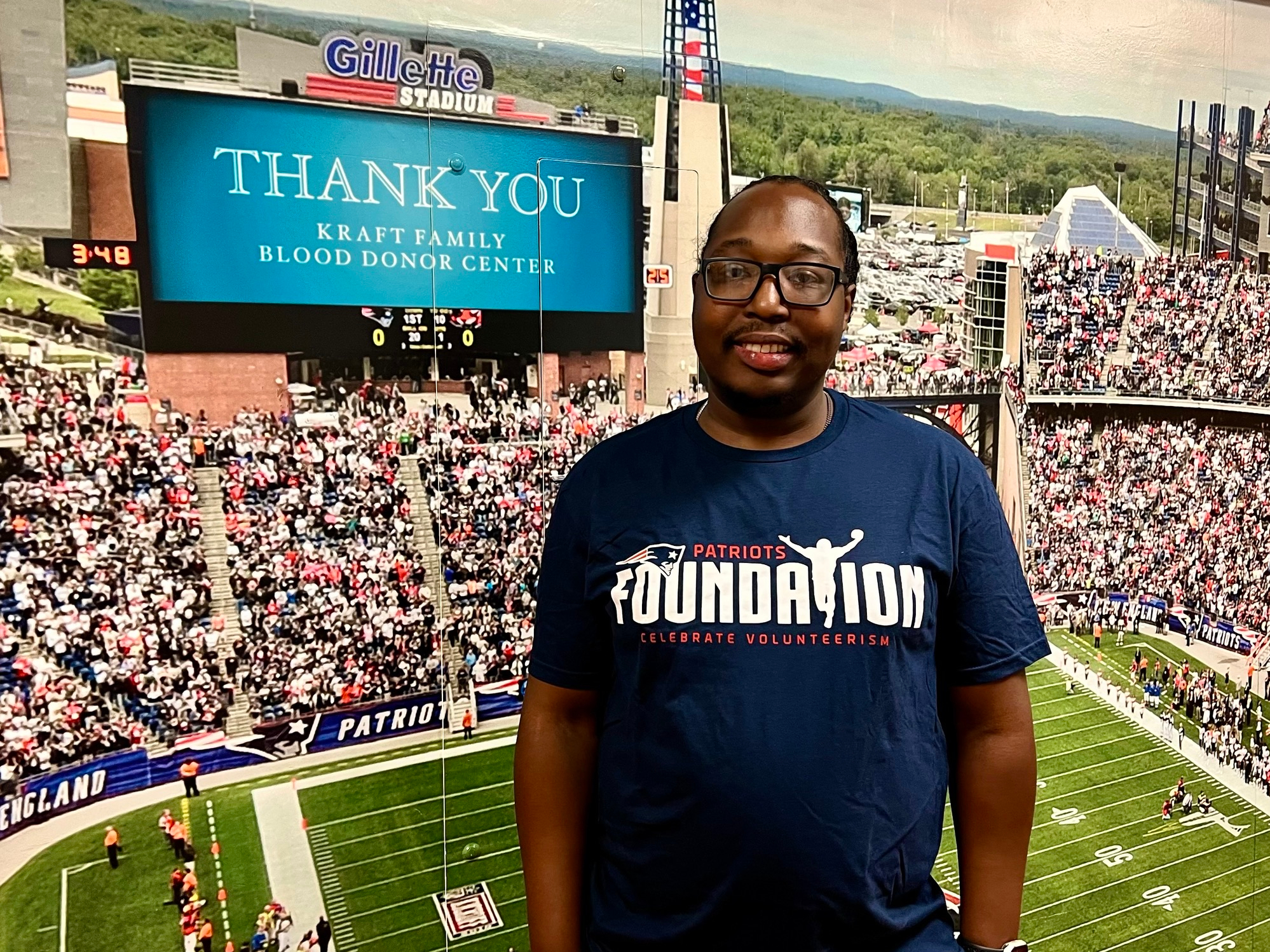

Brunel Etienne Jr. at the Kraft Family Blood Donor Center, where he receives regular blood transfusions to treat symptoms of sickle cell disease

For as long as Brunel Etienne Jr. can remember, he has lived in pain due to sickle cell disease.

“When I was younger, the pain would be more prominent,” said Etienne, 31, who regularly receives blood transfusions at the Kraft Family Blood Donor Center to help manage his symptoms. “As I got older and went through transfusions, the care I got from Brigham and Women’s helped me with my pain.”

Etienne is one of over 100,000 people in the United States living with sickle cell disease (SCD), a condition resulting from a mutation in the hemoglobin molecule, the protein in red blood cells responsible for carrying oxygen throughout the body. Rather than healthy, disc-shaped red blood cells, the mutation causes elongated “sickle” shaped cells that can easily get stuck in blood vessels — limiting circulation of blood and oxygen to different parts of the body.

When this happens, it can cause a number of serious complications and severe pain. “Like little heart attacks all around the body,” said Sean Stowell, MD, PhD, medical director of the Kraft Family Blood Donor Center and Transfusion Medicine at Brigham and Women’s.

Since the 1960s, the life expectancy of those with the disease has risen from 10 years to about 40 or 50 years, Stowell explained, in part due to increased awareness that led to the development of new therapies. However, SCD is lifelong, and the only known cures — bone marrow transplantation or gene therapy — can be expensive and not widely available.

Because of this, many patients rely on regular blood transfusions to improve their quality of life and mitigate the harshest symptoms. Although transfusions do carry some risk of an adverse reaction, they can lower the likelihood of SCD complications like strokes and acute chest syndrome, which occurs when blood flow to the lungs is limited.

“It’s really difficult to manage pain,” said Stowell. While transfusions are “not typically used to manage pain specifically,” he explained, they can help, along with medication.

Sometimes, Etienne said, the pain is worsened by certain conditions, such as when he is outside in cold weather. “I can’t be out in the cold for 15 minutes,” he said. “If I am, pain in my extremities will be an issue.”

“I do take medications, but it doesn’t necessarily help with the pain,” he added. “The thing that helps me through my pain is the chronic blood transfusions I go through every eight weeks.”

Each transfusion Etienne and other sickle cell patients of the Kraft Center undergo uses up to 14 units of blood, all from donors, and all of which must be an appropriate match for the patient to avoid causing a serious, sometimes life-threatening, reaction.

Genetic differences between donors and recipients can lead to transfusion complications. “One of the challenges and the reasons that the reactions occur more frequently in patients with sickle cell disease is that blood donors on average tend to be Caucasian, and the recipients are generally of African descent,” said Stowell. “Science is still working to understand why this occurs. It’s likely the answer lies in genetics, but until we know for sure, increasing the pool of donors from diverse backgrounds can only be a beneficial thing for those who need a transfusion.”

Historically, sickle cell disease more often affects Black individuals, who are more likely to carry the gene that causes it. Racial inequity in health care, along with the lack of sickle cell awareness and research, has created barriers to receiving treatment for many debilitated by the condition.

Noticing the need for further advancements in treatment was one of the reasons Stowell first became interested in sickle cell disease while in medical school. “It was clear that these patients had a horrible disease, and there was really not a lot we could offer,” he said.

Today, much of his focus is on measures that will increase the safety and efficacy of blood transfusions, a treatment that would be impossible without blood donors. The number of Black blood donors is disproportionately low.

To those who choose to donate blood, Etienne said, “You’re not only helping me, but you’re helping other patients who have sickle cell. Your donations help me and other patients tremendously.”

All blood and platelet donations made at the Kraft Family Blood Donor Center directly benefit patients at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Center. Donors can make an appointment to give blood or platelets at the Kraft Family Blood Donor Center (open Tuesday through Sunday) by calling 617-632-3206 or emailing BloodDonor@partners.org. Walk-ins are welcome at the center, which is located at 35 Binney St. To donate closer to home, view a list of upcoming mobile blood drives.

3 Responses to “Blood donors serve as important lifeline for sickle cell disease patients”

As a regular blood donor, I wish my donations could help patients like Etienne. While very informative, this article could do more to highlight and attract the appropriate donors to help with sickle cell related transfusions. It isn’t until the bottom of the article it speaks to this need. Just a thought.

Likewise, having been a regular blood donor for years, because I am white, are my donations eligible to help sickle cell patients? Because I am white, would they be disqualified because of that? I am very sorry if that is the case, it seems like a cruel trick of nature.

Fortunately, all donated blood, regardless of the race of the individual donating, is eligible for meeting the transfusion needs of all patients, including patients with sickle cell disease! We are incredibly grateful for all individuals who donate blood.

To increase immune compatibility between donated blood and a recipient, blood types are examined. For patients who receive blood on a regular basis, such as those with sickle cell disease, blood types beyond the common ABO blood types are tested to reduce the likelihood that an immune response to transfused blood will develop, as these patients require repeat transfusions.

On average, individuals of African descent are more likely to be a full match for patients with sickle cell disease, but others can be a match as well! Because the probability of a match for a patient with sickle cell disease is more common among donors of African origin, we have encouraged those of African descent to donate to increase the likelihood that we will have a good match for our patients with sickle cell disease. However, this, once again, doesn’t mean that blood from other individuals who donate will not be a great match for our patients with sickle cell disease. I am white and my blood type happens to be a good match for many patients with sickle cell disease!

Comments are closed.