The Study and Use of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation to Help Patients

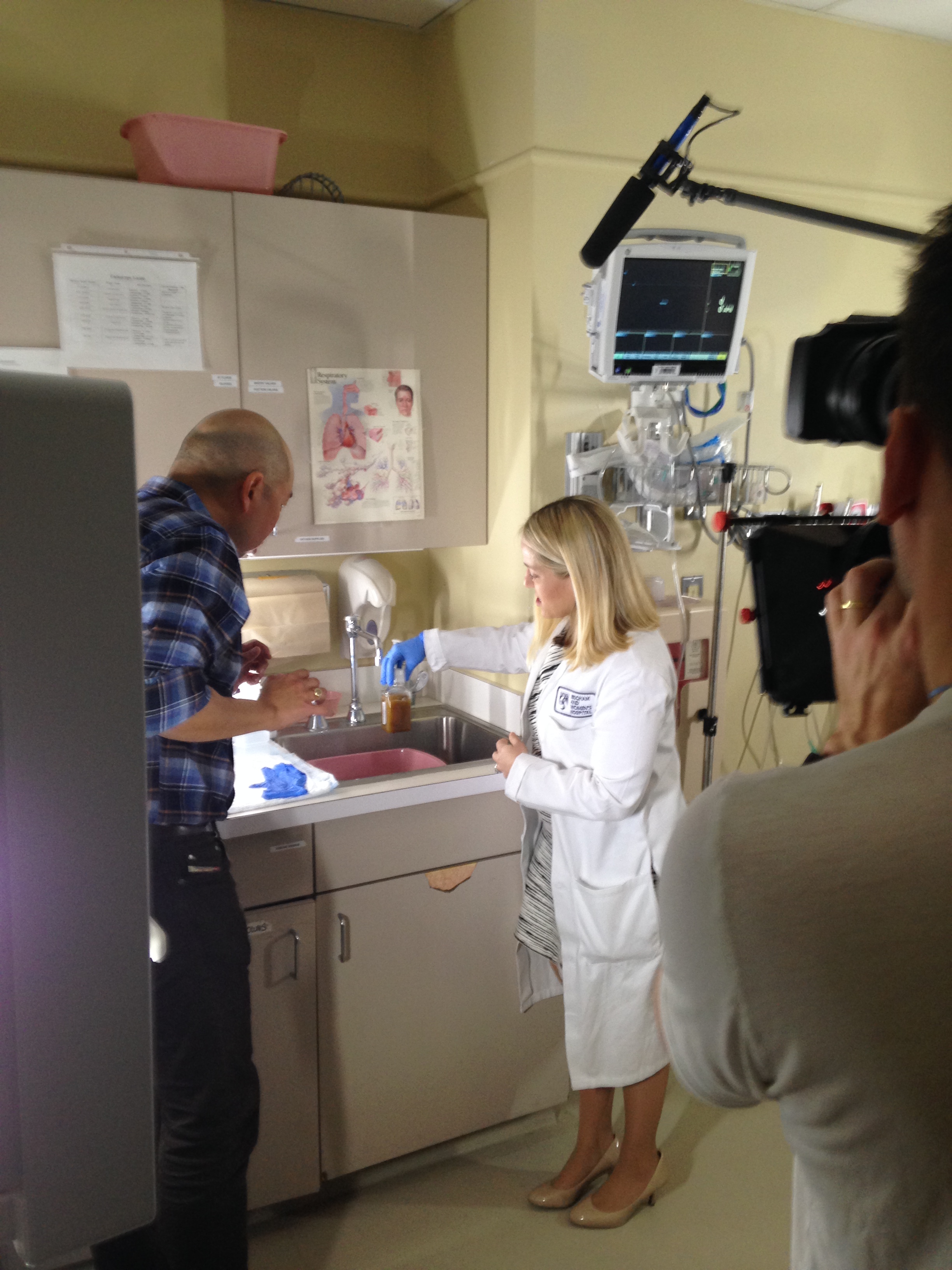

Jessica Allegretti speaks with BBC reporter Giles Yeo about FMT.

When Jessica Allegretti, MD, MPH, was a resident, she cared for a patient with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) whose words ended up shaping the path of Allegretti’s career.

The patient told Allegretti that she would not consider surgery to treat her IBD—which is defined by chronic inflammation of the digestive tract—unless she could get a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) as part of her treatment. FMT is currently being tested in more than 90 research trials as a potential treatment for a variety of diseases and conditions, including IBD.

Presently, the only clinical application of FMT is to treat patients who have experienced three or more episodes of C. difficile (C. diff) or for patients who do not respond to antibiotics. C. diff is an infection that causes symptoms ranging from diarrhea to life-threatening inflammation of the colon. During FMT, fecal matter from a healthy stool donor is instilled into the colon of a patient through a colonoscopy to displace disease-causing bacteria and fight the infection.

As a medical resident, Allegretti didn’t know about the procedure, but after she researched it, she became immediately interested in the potential of FMT as a possible therapy for IBD.

“At the time, it was viewed as almost science fiction,” said Allegretti, who treats patients and performs clinical trials as part of BWH’s Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy. “In 2013, the first controlled trial came out in the New England Journal of Medicine showing that FMT was extremely effective at treating C. diff, and it took off from there.”

As a first year fellow at BWH, Allegretti helped to found the hospital’s FMT program, with support from her mentor and Crohn’s and Colitis Center Director Joshua Korzenik, MD, as well as Endoscopy Center leadership and the Division of Infectious Diseases. She is currently the only clinician at BWH who performs FMTs and does three to five of these procedures each week, a rate that has been increasing exponentially in the past four years. At the Brigham, one FMT yields a 95-percent success rate of curing C. diff (compared to the reported success rate in scientific literature, which is about 90 percent). Many other major academic medical centers also offer FMT.

Each patient who is a candidate for FMT goes through a detailed consent process, during which Allegretti discusses what to expect. From there, OpenBiome—a nonprofit stool bank—sends the frozen stool sample, which Allegretti instills into a patient via colonoscopy. Patients go home right after the procedure, similar to a routine colonoscopy.

“We know if it’s worked within 72 hours; the response is quite quick,” she said. “The symptoms of loose bowel movements or diarrhea go away and remain away. We provide counseling for patients to avoid unnecessary antibiotics, which are a big part of what’s driving C. diff infections.”

In addition to time in the clinic, Allegretti is involved in several clinical trials, including one that is testing the effectiveness of a single FMT in improving liver inflammation among patients with primary sclerosis cholangitis—a chronic disease that slowly damages the bile ducts. She also recently worked on a dose-finding study of fecal capsules, learning that lower doses are just as effective as higher doses when it comes to curing C. diff. She is beginning work on a study that will look at the use of FMT to treat obesity, which will include an initial transplant via colonoscopy and oral capsule maintenance therapy.

Though fecal capsules are not appropriate for all FMT candidates, Allegretti believes they are the future of FMT.

“Capsules allow us to not only offer FMT to a broader patient population in a more timely and cost-effective manner, but they let us do better research,” she said. “For example, for chronic disease, one FMT is not going to be enough, but with capsules, we can provide the maintenance therapy that is needed.”

Allegretti says the most rewarding aspect of this work are the results.

“Some patients with C. diff suffer for years and are ostracized by family and friends or they feel they can’t leave their houses,” she said. “They have an FMT and feel better almost immediately. There is nothing more rewarding than seeing these patients break the cycle of recurrent C. diff. FMT is not going to be a cure-all for all diseases, but it allows clinicians and researchers to better understand the role bacteria play in many gastrointestinal diseases and to make more sophisticated, targeted therapies. It’s an exciting therapy to be able to offer and study.”

Leave a Reply